| Verifying Division Orders | Practice Areas | Cases | Fees | Contact | About |

As

an oil and gas title attorney, my primary area of

practice is deed examination-- i.e. reading old

deeds and interpreting what they mean under

current Texas and New Mexico law. Because every

deed is different, there is no end to the types of

mistakes drafters and interpreters can make. The

following is a non-exhaustive list of common

sources of title disputes.

Very few cases go to trial. Instead, most settle through mediation. In a mediation, each side sits in a separate room. The mediator walks back and forth, twisting arms until there's a settlement. Mediation is very flexible. The parties can settle a dispute however they want. In court, results are often black and white,, For example, in a lawsuit over ownership of minerals and past royalties, the winning party will recover both in court. In a mediation, one party could choose to keep a larger share of the minerals in exchange for a smaller share in the royalties.

In some cases, the parties can agree to arbitrate disputes. Arbitration is a form of abbreviated trial. The parties choose an arbitrator and the arbitrator decides the scope of discovery. There are no juries and there is no appeal. Arbitration is sometimes expensive, but it is fast because discovery is often limited and certain because appeals are extremely restricted. Although arbitration is rare in title disputes, the parties can choose to arbitrate at any time.

When mediation fails or arbitration is unavailable, cases go to trial. In court, judges decide law and juries decide facts. Deed interpretation is almost always a legal issue, not a factual one. Most title disputes are therefore resolved without a jury. Instead, the parties ask a judge to rule through a declaratory judgment or trespass to try title.

In Texas, there are two types of title lawsuits: trespass to try title and declaratory judgment. Although trespass to try title and declaratory judgment are two sides of the same coin, there are critical distinctions. Texas appeals courts have reversed and rendered trial courts when the lawyer used the wrong cause of action.

Trespass to try title is a possessory remedy. It relies on the fiction that a plaintiff can "trespass" on land to force a trial on title. Because trespass to try title is possessory, some courts hold it does nonpossessory royalties and leased minerals. Other courts disagree. They follow the Texas Property Code's cryptic instruction, "A trespass to try title action is the method of determining title to lands."

A declaratory judgment asks the court to declare the meaning of a deed or the ownership of property. Declaratory judgments apply to possessory or nonpossessory interests. They are not subject to any time limitations. A court can declare the meaning of a 3 year old deed as easily as a 30 year old deed. The declaratory judgment statute provides for attorneys' fees, but the trespass to try title statute does not.

Because there is a split in the courts of appeal as to whether trespass to try title or declaratory judgment is the proper cause of action, pleading both is the best practice. Other causes of action, like a suit to quiet title or slander of title, are largely redundant.

Before issuing payments, most oil and gas companies require landowners to sign division orders. Signing division orders indemnifies the oil company against errors in payment. If you own a 1/50th interest in the well, but you sign a division order saying you own a 1/100th interest, you won't be able to sue the oil company for the difference.

Because of that, a lot of people think division orders are silver bullets. In every oil and gas case, one side alleges the other waived their rights by signing a division order. That is not the law. Division orders are extremely important to oil companies, but they make no difference in disputes between landowners. Division orders do not ratify or convey title. They are binding until revoked. They can be revoked at any time.

That doesn't mean landowners can ignore division orders. Landowners who are paid incorrectly lose their rights to unpaid royalties after a period of years. If you don't verify your division order when the well first produces, you may never notice the problem. Almost every title dispute could be resolved if landowners checked their division orders at first production.

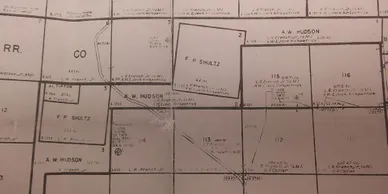

For a detailed explanation of how to calculate your division order interest, see my page on verifying division orders or click on the image of the division order here.

Landowners and lawyers alike fear the Duhig Rule. Under the Duhig Rule, a seller who reserves a mineral interest loses that interest if he does not own enough to make the buyer whole. For example, suppose a seller owns 1/2 of the minerals and signs a deed selling "all of the land, save and except 1/2 of the minerals, which are reserved to the seller." The seller does not own enough to satisfy the grant to the buyer ("all of the land"). Therefore, the seller loses the minerals he attempted to reserve.

The Duhig Rule still is slowly falling out of favor. Numerous courts have created large exceptions. In the example above, if the seller's deed said "subject to all reservations of record," then Duhig would not apply. The same would be true if the deed said "all of my interest in the land, save and except 1/2 of the minerals" instead of "all of the land save and except 1/2 of the minerals." These narrow exceptions within an already narrow rule make Duhig problems easy to miss.

The Duhig Rule may not be long for this world. Under current Texas law, recording a deed puts everyone on notice of its contents. Voiding a reservation to make the buyer whole doesn't make sense if the buyer has notice that the grant is ineffective. Furthermore, when courts interpret deeds, they try to give meaning to all of its clauses. Duhig forces them to do the opposite. It's only a matter of time until the right case brings this tension to a head.

For many years, all oil and gas leases had a 1/8 royalty. In the 1970s, landowners realized they could ask for more. Today, most leases have 1/4 royalties. Leases in marginal areas commonly have 1/5 or 3/16 royalties. Because most royalties were 1/8 for so long, landowners bought and sold fractions of the "usual 1/8 royalty." Thanks to these deeds, the ghost of the 1/8 royalty still haunts Texas law.

Courts have struggled to reconcile deeds selling "1/2 of the usual 1/8 royalty" with modern leases that reserve a 1/4 royalty. Under a modern 1/4 royalty lease, the owner of "1/2 of the usual 1/8" actually owns 1/2 of 1/4. These deeds create "floating royalties," so called because they increase with the royalty in the underlying oil and gas lease. The opposite of a floating royalty is a "fixed" royalty. A deed selling "a 1/16 royalty" will not change with the underlying oil and gas lease.

The Texas Supreme Court recently changed the status of fixed and floating royalties. Although the law has been clarified, few oil companies have corrected their division orders. It's likely that thousands of landowners with floating royalties are being incorrectly paid on a fixed basis. You should contact an attorney if you suspect you may be one of them.

Some title examiners may find implied reservations when deeds are poorly written. Implied reservations are disfavored under Texas law. Deeds are construed to convey the greatest possible estate. Reservations are interpreted strictly and narrowly. If a seller owns 1/2 of the minerals and signs a deed selling "all of my minerals, being 1/4," the seller has sold 1/2 of the minerals. He just described the conveyance incorrectly.

In one of my recent cases, a deed conveyed "1/8 [of the minerals] owned by [the sellers]." When the deed was signed, each of the two sellers owned 1/8, for a total of 1/4. The sellers argued the deed conveyed 1/8 of the seller's 1/4, or 1/32. We successfully argued the rule against implied reservations meant the deed conveyed both sellers' 1/8 interest, for a total of 1/4. The phrase "owned by the sellers" was not an implied reservation, it was a reiteration that the sellers owned what they were conveying-- i.e. "1/8 [of the minerals] owned by [the sellers]."

Because reservations by implication are disfavored, many deeds have unintuative results. An experienced title attorney can spot these common pitfalls and maximize the client's royalty. You should not rely on the oil company's title lawyers to do this for you.

When someone dies without a will, their property is distributed through the laws of intestacy. In Texas, the surviving spouse inherits a 1/3 life estate in all separate real property. The children inherit 2/3 outright the remainder in the 1/3 life estate. Life tenants are entitled to possession during their lifetimes and interest the estate.

This simple distinction causes major problems in oil and gas. Royalty payments under an oil and gas lease are considered payments for the sale of the corpus-- i.e. the principal. They are not interest (note the IRS has a more nuanced view). Because royalty payments are principal, they belong to the remainderman. Because the life tenant has the right of possession, she is allowed to possess the remainderman's royalty payments, but she is not allowed to spend them,

There are exceptions to this rule. The open mines doctrine allows life tenants to keep payments on production when the land was leased prior to the creation of the life tenancy. Similarly, an oil and gas lease signed by a life tenant will not bind the remaindermen. Regardless of nuanced exceptions, oil companies frequently pay royalties to the wrong people-- or they don't pay them at all.

A good title lawyer can resolve these problems with a family agreement or a stipulation of interest. Outdated rules of real property shouldn't prevent landowners from being paid.

Texas courts recognize a distinction between sales of minerals in the "land described" and minerals in the "estate conveyed." A deed conveying "all of my interest in the farm together with 1/2 of the minerals in the land described" will sell 1/2 of the minerals. A deed conveying "all of my interest in the farm together with 1/2 of the minerals in the estate conveyed" will sell 1/2 of whatever the seller owned.

When a deed refers to the "land described," it refers to the metes and bounds of the property as it exists on the ground. When a deed refers to the "estate conveyed," it refers to the legal interest of the owner. Therefore proportionate reduction makes sense in the latter case.

This subtle distinction is very easy for title examiners to miss. It turns on old, esoteric interpretations of four words buried in hundreds of pages of deeds. In oil and gas, subtle mistakes like this can cost landowners large amounts of money. Landowners shouldn't rely on the oil company to get it right for them.

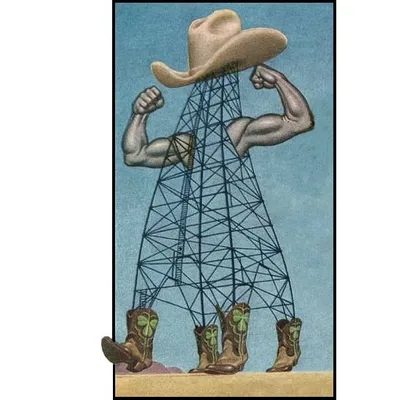

When an oil company sends you an oil and gas lease, the first question is "Should I sign?" The answer is almost always yes. Unless you a large portion of the minerals, they're going to drill with or without you. Unleased mineral owners are not paid until the well reaches payout. Payout occurs when the driller recovers all drilling, completion, and operations costs. If an unleased mineral owner is not on a drillsite tract, he will never be paid. On vertical wells, drillsite tracts are wherever the wellbore goes into the ground. On horizontal wells, drillsite tracts are any tract the wellbore crosses.

Although you should always sign oil and gas leases, you should never do so without negotiating the terms. Every material term in an oil and gas lease is negotiable. Before signing a lease, you should make sure you're receiving a 1/4 royalty and a fair bonus. Bonus prices are a closely guarded secret. They can range from a few dollars to tens of thousands of dollars an acre. You won't know whether you're receiving a fair bonus unless you hire someone who knows the market.

Oil and gas leases should also contain multiple clauses to ensure continuous development. Leases remain in effect until production terminates. Well negotiated leases terminate as to nonproductive acreage after a period of years. Without termination clauses, a single well producing a barrel a day can hold the lease in effect as to all acreage for many years. Landowners should want their leases to terminate on nonproductive acreage. Termination will encourage other drillers to produce the land and future oil and gas leases will contain then-current clauses and rates.

To be valid, deeds must have valid property descriptions. Without a property description, a deed is void. A void deed has no effect-- it is dead on arrival. A person who buys property with a void deed has more rights than a squatter, but not by much.

Valid property descriptions describe the land by section and block, by metes and bounds, or by reference to an older deed with a valid description. Invalid property descriptions include colloquial names, street addresses, and Tax ID numbers.

Old metes and bounds descriptions are often unreliable. The surveyors often marked the corners with old wagon wheels, a neighbor's fence, or a driven gun barrel. Some section and block descriptions are also problematic. If a section does not run north to south and east to west, a description of the "southeast quarter" may be ambiguous.

The Texas oilfield has seen its share of fraud. One of the current scams is "leasing" non-participating royalties. To understand the scam, you have to understand that not all landowners sign oil and gas leases. Only mineral owners sign oil and gas leases. Royalty owners are paid a fraction of production based on the mineral owner's lease. The royalty lease scam works because royalty owners don't realize they have no leasing rights.

The fraudsters target non-participating royalty owners and offer them a "bonus" in exchange for signing a "paid up lease." The so called lease contains numerous oil and gas lease terms and is sometimes formatted to look like an oil and gas lease. Many royalty leases contain lengthy arbitration clauses. The royalty lease is secretly intended to be a term royalty deed. The fraudsters tell royalty owners they are leasing, but they tell oil companies they are buying.

If you suspect you may have signed a royalty lease, you should call an attorney immediately. An experienced oil and gas attorney can spot this scam quickly. There is no such thing as a "lease" of royalty in Texas or New Mexico.

Adverse possession is also known as "squatter's rights." It's very common. In fact, the Northwest corner of the Texas panhandle is 2.3 miles west of its intended location. The misplacement was caused by a surveying error. Texas blocked New Mexico's statehood until the territory surrendered the 2.3 mile strip. That may not sound like much in west Texas terms, but that 2.3 mile strip is 310 miles long and it gets wider toward Midland.

That 2.3 mile strip includes high value in oil and gas. Fortunately for Texas, it's a sovereign state and it didn't give New Mexico a choice. For mere mortals, surveying errors like the 2.3 mile strip are among the common causes of adverse possession. In oil and gas, adverse possession only works in two scenarios: 1) when a squatter on the surface claims minerals owned by the surface owner, and 2) when an oil company continues operating a well after the lease has expired.

Adverse possession does not apply to minerals which have been "severed" from the surface estate. Minerals are severed when they're sold or reserved separately from the surface. If you own the surface and the minerals, you should split them up with a trust or family partnership. Doing so will prevent future adverse possession. It will not, however, prevent past or current adverse possession. If a squatter came onto your land in 1998 and you put the minerals in a trust in 2001, the severance will not oust the squatter.

Adverse possession does not apply to royalties. Royalty owners have a right to receive payments, they do not have a right to enter the property physically. Therefore possessory remedies like adverse possession are inapplicable. The same is true for minerals under an oil and gas lease. Oil and gas leases are deeds. When you sign an oil and gas lease, you are selling your minerals to the lessee and reserving a royalty. Because minerals under lease are royalties, they are not subject to adverse possession.

Bold labels are required.

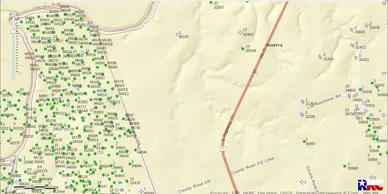

Abilene Office

1049 N. 3rd St

Suite 200

Abilene, Texas 79601

Phone :325-691-0370

Fax: 325-692-8107

Map & Directions

Houston Office

2402 Pease Street

Houston, Tx 22003

Phone: 325-691-0370

Map & Directions